In a few weeks’ time I will be taking part in the Local Word festival in Geelong, and speaking about my novel One for the Master. I’ll be joining a panel of writers who have set their works on, and been influenced by, Geelong, the Bellarine Peninsula and the Surf Coast – speaking broadly, Wadawurrung Country. The panel will comprise actor and playwright Tom Molyneux, Sudanese writer Kgshak Akec, and myself, with panel chair, Rhett Davis.

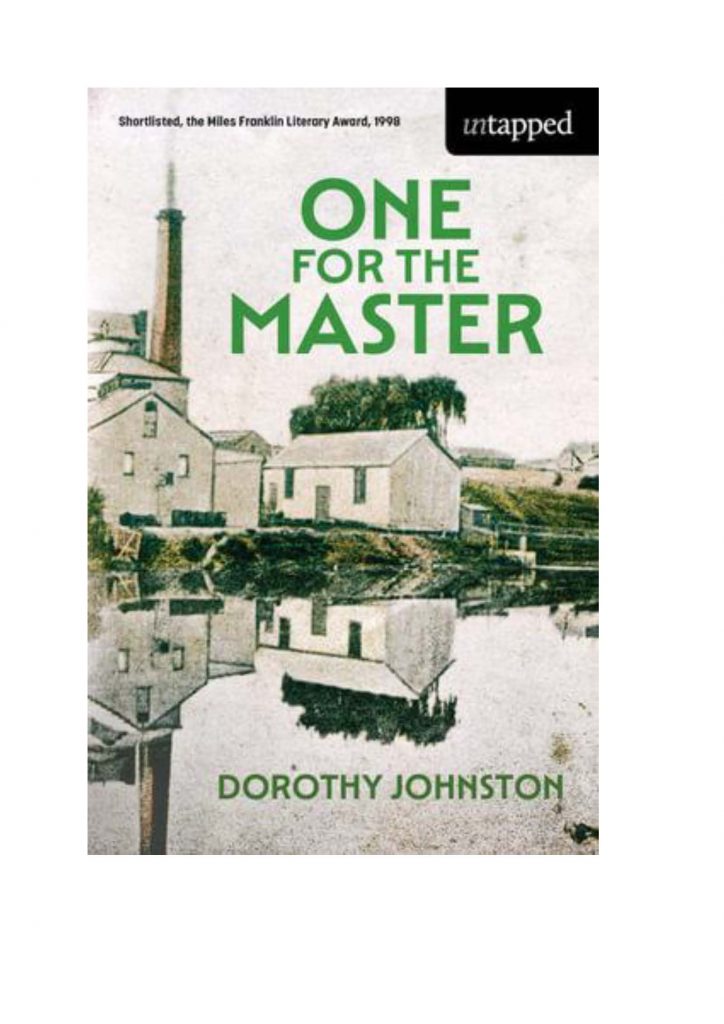

One for the Master tells the story of the collapse of the woollen industry in Geelong. Geelong used to be called the Bradford of the south, and this old, dirty, proud industrial city was the one I was born and grew up in, in the 1950s and 60s.

My family first lived in West Geelong, then moved across the river to Belmont, within walking distance of the Barwon River. My sister and I used to escape down there to a place we called the swamp. Swampy it was, muddy and marshy on the river bank. It was wild and lonely and we seldom saw anybody else. It would never have occurred to our parents that we needed adult supervision or accompaniment.

Many years later, after I had moved first to Melbourne then to Canberra, I came back for a visit and was staying at my parents’ house with my daughter, then a toddler. I decided to take her for a walk in the pram along the river bank. It was a misty morning, autumnal, cool. We watched the mist rising from the river. After we’d gone a little further, I noticed huge shapes appearing out of the mist. I knew them to be part of an abandoned woollen mill. It looked ruined, ghostly, yet it had its own kind of dignity. I wondered why no one had pulled it down and built something else, the land along the river surely being valuable.

I began talking to my father about the ruin. His older sister had once worked in a woollen mill. I tried to talk to her as well, but she wasn’t keen to re-live her experiences. My father had lived all his life in Geelong and had a wide circle of acquaintances. It was through them, and through the fine resources of the National Wool Museum, that I began building up a picture of what life had been like in the mills. I heard stories of women’s hair being pulled out by the machines, of being scalped, of constant back pain, of the paternalistic approach of the mill owners, which had its good and bad side, then of the demise of the industry. Synthetics took over from wool. Then came the tariff reforms of the 1970s.

One for the Master is fiction. It does not set out to give a definitive account of life in Geelong’s woollen mills. Though loosely based on the Returned Soldiers Mill, my mill is an imaginary place, peopled with characters that grew out of my imagination. I would not have written it had it not been for that morning in the mist, and I certainly wouldn’t have written it had I not had access to the first hand accounts of working life held in the wool museum. Once begun, though, the novel took on a life of its own.

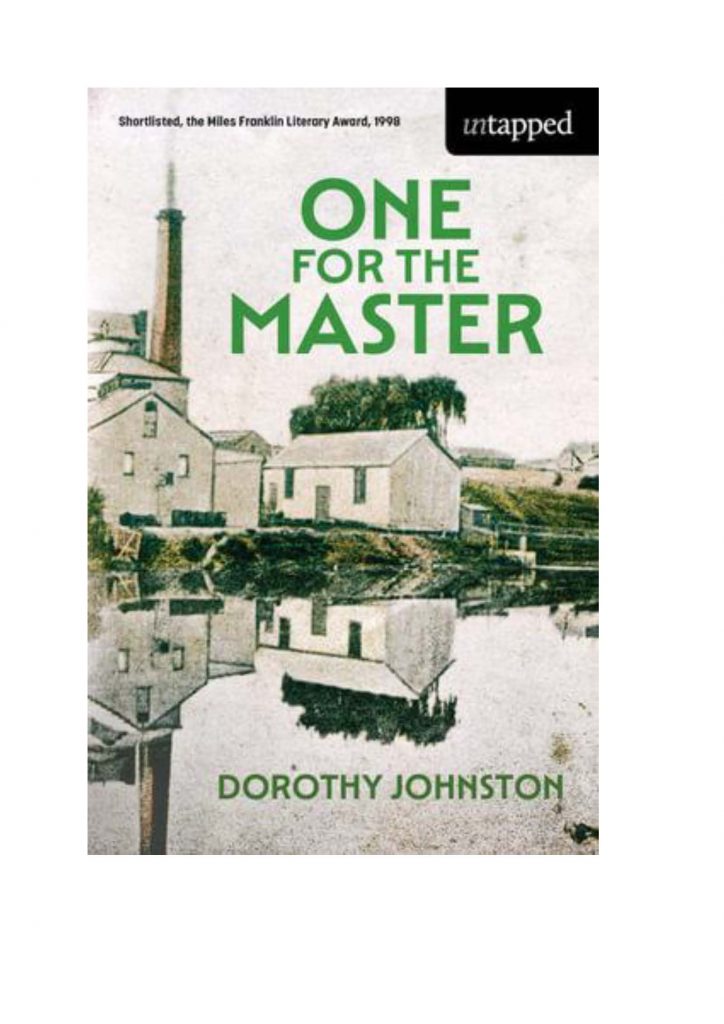

One for the Master was first published in 1997 and shortlisted for the 1998 Miles Franklin Award. It has recently been re-published as part of the Untapped Project, for which I am very grateful.

The Untapped project is a marvellous initiative which gives readers access to long lost books in both print and digital form.

More than 150 titles are available to borrow from libraries and to purchase. Partners in the project include the Australian Society of Authors, National State and Territory Libraries, the Australian Library and Information Association and Ligature Press.

Amongst those 150 titles are the 7 Writers Anthology, Canberra Tales, first published by Penguin in 1988.

This article, published in the Canberra Times today, April 15, tells the story of how 7 Writers came into existence, and how we continued meeting as a writers’ group for over 15 years.

My novel, One for the Master, published by Wakefield Press in 1997 and short-listed for the 1998 Miles Franklin Award, has also been re-published as part of the Untapped Project .

It’s wonderful to be able to hold this long out of print novel in my hands again. Thanks to all those involved in the project, in particular Airlie Lawson and publisher Matt Rubinstein.

The Lodeman is the fourth book in my sea-change mystery series set in Queenscliff, Victoria. It was to have been launched in October 2021, but the launch has had to be postponed until February next year.

It’s about the death of a sea pilot. Lodeman is an old word for pilot or navigator, from the same root as lodestar, meaning a star that is steered by.

My lodeman is washed up on the shores of Port Phillip Bay.

The Port Phillip Sea Pilots have a long, honourable tradition of piloting ships through the treacherous Port Phillip heads and in to Melbourne. It seems almost a crime against nature when one of them, respected Captain Delraine, is found dead by drowning on the beach close to their operation centre. Queenscliff constable Chris Blackie would have had little to do with the investigation into Captain Delraine’s death but for the fact that a friend of his found the body.

A Detective Sergeant looking for easy answers spurs Chris Blackie to ask questions behind the sergeant’s back and to uncover corruption, greed and high-running passions before the case is solved.

In 1983, when West Block was first released, there had been very little prose fiction set in Australia’s national capital. The first published novel to be set in Canberra was Plaque With Laurel, by M.Barnard Eldershaw, the pen name of Marjorie Barnard and Flora Eldershaw. It appeared in 1937. TAG Hungerford’s Riverslake was published in 1953, then there is a gap of twenty-four years till Robert Macklin’s The Paper Castle in 1977. Blanche d’Alpuget’s Turtle Beach, 1981, was followed two years later by Sara Dowse’s West Block. West Block was and remains a pioneering work.

In Ric Throssell’s biography of his mother, Katharine Susannah Prichard, he notes her comment that Canberra was ‘like a town made by Pinocchio. All that neatness and prettiness, so far removed from the struggle for existence.’

Prichard’s view was a false one, as people who have lived in Canberra for any length of time will know, but probing beneath the false view, forging a place for Canberra in Australian literature, took courage and effort, and was quite often received with a hostility which may seem strange to readers in 2020.

I consider it a privilege to review a re-issue of West Block almost forty years after its first release. The novel is as timely now as it was in the 1980s, combining, as it does, unforgettable insights into the workings of federal politics with an imaginative study of flawed human lives.

West Block begins with a prologue dated December 1977, then is divided into five sections, taking readers into the hearts of five very different characters.

George Harland has risen to a senior position in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet and has served for more than two decades under Coalition governments, compared with only three under Labor, these three being the Whitlam years. His commitment is to the smooth running of government, rather than policies or political visions. Then his daughter Marion announces she is leaving her husband and her two young sons. Her politics are far to the left of her father’s and George suddenly finds himself re-considering his life and the work which has formed such a large part of it. How far this re-consideration takes him is left for readers to decide.

The government is about to decide whether or not to open a new uranium mine. Henry Beeker, lower in the hierarchy than George Harland, but still a senior, experienced public servant, brings all his skill and intelligence to bear on ensuring that the decision is a responsible one. A trip to Brussels almost ends in disaster, while back home, Beeker and others work through draft after draft of their submission. Then they have to face the Cabinet.

Catherine Duffy is caught up in the chaos that was Saigon as the city fell to the North Vietnamese. Catherine has got to know a number of Vietnamese refugees as part of her work with overseas students, and become friends with one family in particular. In 1975 she is sent to Saigon to assist with the evacuation of children, and is able, through an act of personal courage, to help one of her friend’s relatives to escape.

Economist Jonathan Roe seeks compromise with the hard-liners in his own department, as well as in Treasury. A personal crisis threatens to undo him, but his outlook on life is profoundly changed by the birth of a child.

And Cassie Armstrong, head of the small, dedicated Women’s Equality Branch, watches as their ability to bring about change for women is eroded and side-lined. Exhausted and demoralised, Cassie finally reaches breaking point.

West Block, the building, is the novel’s sixth protagonist, containing a host of minor characters as well as the main ones. In her Author’s Note, prefacing the new edition, Dowse says, ‘the building itself galvanised me. The minute I walked into it I wanted to write its story, but now that I was in a position to, I was up against the prejudice against Canberra, most particularly Canberra’s public service.’

Dowse began working in West Block when she joined Prime Minister and Cabinet to head their inaugural Women’s Affairs Section, where she remained until 1977. She resigned in protest after the unit was moved to another department.

Readers first meet West Block on a summer night when ‘the naked white building stood out like an iceberg on a northern sea’. Collapse is imminent, but we must wait to discover why.

In lyrical prose and images that are crystal clear, Dowse celebrates Canberra’s physical beauty through each markedly different season. ‘Russet leaves brushed against the window. The fog had lifted; the sun shone white and gold.’ Autumn gives way to winter and winter to spring, while inside the departments and the Parliament, bureaucrats who genuinely believe their role is to serve the public struggle against bitter disappointment.

In this beautifully produced new edition, Dowse’s voice speaks to readers across the decades, in a voice that is at once intimate, authoritative, sad, and yet hopeful too.

This review was published in the Canberra Times on September 26. As I say in my review it was a privilege to be asked to write about West Block and to revisit the novel after nearly forty years.

Here’s another lockdown poem, partner to one I wrote in an earlier post.

Smiling Behind Masks

with thanks to Marilyn Chalkley, who gave me the idea

Smiling behind masks

is becoming something of an art.

Smiles starting with the eyes

move downwards to a barrier

of cotton or of polyester,

a definite, clear line in daylight,

less so before sunrise

when I walk by the sea.

Masks cover more than half a face,

while the rest must carry

all expressions, or else hint at secret ones.

Smiling behind masks

is becoming something of an art.

People have chosen many shades,

from black to white, flowers and swirling abstracts,

football colours marking tribal loyalties.

Eyes speak, making up for hidden mouths,

for noses which might wrinkle at a joke well told.

A loosening of skin around the temples,

at the hairline, becomes a message

and a kind of grace.

Smiling behind masks

is becoming something of an art.

I wait beside the other sunrise walkers

staring at the place where sky meets sea.

My dog waits with me. Others, too, have dogs,

minding their own business.

Gold gathers strength on the horizon,

thrusting pink and grey aside.

I sigh behind my mask,

warm air captured then released.

The first morning, like the song says:

the first birds have spoken earlier, while it was still dark,

while I hurried to get ready; coat, then shoes, then this thing

that I breathe in and out behind,

as the gold bursts and the day says, here I am.

In these times of lockdown and uncertainty I am more grateful then ever for the shops that have supported me by selling my books, and by encouraging readers to try them. In this post I want to thank Karen and Paul for their help and enthusiasm. Karen and Paul run the Point Lonsdale newsagency and post office. Last summer it was Karen’s idea to have a book signing day outside the shop, which did very well. Thank you to this small business, and to all small businesses everywhere who support their local artists. The photo is of Karen and myself outside the shop.

I’m very pleased that my novel ‘Gerard Hardy’s Misfortune’ has been longlisted for the Sisters in Crime Davitt Award. Way back in the mists of time, the first of my Canberra crime novels, ‘The Trojan Dog’, was runner-up in the inaugural Davitt Award. Then there were relatively few entries. This year there were 124. Women’s crime fiction is powering ahead in Australia.

My prose muse had deserted me for the moment, but I’ve been writing poems. The first one is called Smiling from a distance.

Smiling from a distance

People smile at one another

from a distance on the beach.

I think we might perfect the shine of distant smiles.

‘Hello,’ we call. ‘Good morning, afternoon, or evening.’

It’s become suddenly important to mark passage,

mark the time, to speak, stranger to stranger

across a measured space.

Waves lift. Light dances on water, water drinks the light.

The beach is still open to walkers,

provided that they walk in ones or twos;

open to surfers sharing drop and curl.

While on the headland, there above me, silhouetted,

a paraglider’s stopped by police in uniform.

He would fly, or as near as he is able,

but stands grounded, his sail filled with air.

Inland, just a little way, my sister walks straight corridors,

locked inside a nursing home.

Yet on the phone she’s cheerful,

pleased that she can walk at all, while many can’t.

I send her a smile across the short, uncoverable distance

separating us. Imagining, I place my feet just so.

Can a smile be measured?

I think the answer is both yes and no.

One and a half metres, repeated like a mantra,

becomes a background to the everyday.

No need for tapes: the eye does just as well.

Four women in a park sit properly, legal distance well observed,

wearing coats and beanies, for the air is cold.

They call out; one laughs, raising her hand to join the conversation.

Across this open human space they smile.

Second hand bookshop under lockdown.

The books form towers, in shadows

by the doorway and around the walls.

We are here, they say, our words are here.

Our spines face outwards to the dim room and closed door.

We are not arranged by date or author,

but known to the old man who has given us a home.

For many years I have been a customer,

coming in from the hot light of Hesse Street

in summer, or in winter,

having crossed the road against the slanting rain.

Always it has been the same inside,

the same smell, old and welcoming.

The owner sits outside on a wooden bench,

eating an ice-cream, affecting nonchalance.

I take a few steps forward, then ask, ‘Are you open?’

‘I might be,’ he says.

I stand on a chair and read titles with difficulty

in the corner furthest from the door.

If I were so rash as to choose one

from near the bottom of a pile

and attempt to remove it,

all those above would fall down and crush me.

It would be a way to go, I think.

For a wordsmith like myself, not a bad way to go.

The owner has come in, still eating his ice-cream

as though it were some kind of prophylactic

or excuse. ‘How are you coping?’ he asks.

I turn awkwardly, careful not to dislodge

by even a puff of breath, the tower

which seems to me now a statement in itself.

‘I’m alright,’ I say. ‘And you?’

‘I’m a bit lost,’ he says.

I nod and point. ‘I’ll have that one.’

It’s not the old friend I imagined finding and re-reading,

but in a bookshop under lockdown beggars can’t be choosers.

We exchange a glance. The old man, keeping his distance, smiles.

The libraries are all shut, of course,

and the proper bookshop up the road.

I pay the princely sum of seven dollars

and leave with my purchase underneath my arm.

Can books transmit the virus?

I hope not. Can I catch it by touching any one of them?

I believe not, but will wash my hands in case.

I realise I wasn’t watching the old man

get down the book I wanted without causing an avalanche.

No doubt he has his methods.

I would like to turn back and ask, but do not.

Instead I climb into my car and drive home.

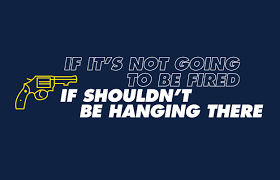

Much as I dislike agreeing with Ernest Hemingway about anything, I find I am in agreement with him about Chekhov’s gun.

Hemingway’s views on hunting and bullfighting would alone be enough to put me off, but when I was staying at the Chateau de Lavigny (a Swiss writers residence) back in 2006, I found a marvellous collection of letters in the library. Famous writers from Europe and the United States had stayed at Lavigny over the years and the extract below is from a letter Hemingway wrote in the 1930s to his German publisher.

Hemingway was nursing a broken arm, having shot ‘a big horn mountain sheep ram, two bears and a bull elk’. Clearly the confinement caused by his injury didn’t suit him, since his letters at that time are full of complaints.

‘I have been here for a month with my right arm broken off clean below the shoulder, so I have not answered your cables or letters. Will you please send me press reviews of Farewell to Arms and some copies of Manner. I have never yet received even one copy of Manner. If you do not treat me better about books and make me more money, I will have to get another publisher.’

Some readers might applaud this forceful attitude, but to me it smacks of the egotism I associate with Hemingway.

So what is it about ‘Chekhov’s gun’ that finds me reluctantly siding with him?

The principle, stated simply, is that writers should not make narrative promises to readers that they don’t fulfil. The image Chekhov famously used was a rifle hanging on the wall.

‘If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.’ (quoted in Chekhov: The Silent Voice of Freedom.)

Not making false promises to readers sounds like a laudable principle, but, to return to the image of the gun, what if there’s not one hanging on the wall, but several? What if the wall is liberally decorated with guns? Should they all go off?

I’m thinking of ‘red herrings’, and the important part they play in crime fiction. Do readers feel cheated when the ‘red herring’ gun fails to go off? I don’t. I don’t mind narrative cul de sacs, or inconsequential characters making cameo appearances.

Some writers do have all the guns going off; their narratives are full of bangs and blows. I’m not that kind: I find constant violent action irritating. As a reader, I prefer to puzzle out things alongside the protagonist (or protagonists). I like room for reflection.

Hemingway mocked Chekhov’s principle and valued inconsequential details. He cited instances in his short stories of characters who appear then disappear without making an obvious contribution to the plot.

I find it a sweet irony that Hemingway managed to break his arm while killing animals for so-called ‘sport’. If the shooting accident had been in one of his stories, rather than something that had actually happened to him, where was the narrative moment for which the accident was a ‘kept promise’ of the kind Chekhov had in mind?

It would be lovely if Chekhov were able to have the last word on this, but unfortunately he can’t.

Hemingway had the last word when he committed suicide by shooting himself at the age of sixty-one. In that sense at least, all the former gunplay, the posturing and complaints weren’t false promises. The gun on the wall did go off many times and the last time it killed him.

photo of Dorothy Sayers

“Time and trouble will tame an advanced young woman, but an advanced old woman is uncontrollable by any earthly force.”

This wonderful quotation is from Clouds of Witness, a 1926 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, the second in her series featuring Lord Peter Wimsey.

I haven’t read Clouds of Witness, so I don’t know who says it, or whereabouts in the novel it comes. I should read it, being myself a lover and writer of mysteries.

I have, however, quoted Sayers’s lines quite often during the last few years. I sent them to a friend after I joined Grandmothers for Refugees. (I’m not grandmother, so I had to become an associate member.)

But I’m old enough to be a grandmother, which is the point.

I have nothing against young women. Many whom I meet are brave and wonderful, but I admit to indulging a private smile at the picture of them tumbling, gracefully, regretfully, at hurdles, while we grannies and would-be grannies, with our grey hair and whiskered chins march on.

I’m particularly mindful of the need to keep marching on as the launch of my twelfth novel approaches. I should feel proud to have got this far, and I do. I should feel grateful to all the people who have helped and continue to help me, and I definitely do. I look back at the hurdles where I fell and lay there panting, then got up again and stumbled on.

Sayers says we advanced old women are unstoppable by earthly forces. Of course it’s conceited to claim we are advanced. But I think we’re entitled to the claim when we look back at the hurdles and realise that any one of them might have been the end.

When I think of earthly forces, I mainly think of human ones, that did not want me to succeed. I don’t think of the wind and rain, the wild storms that have never been my enemies.

Thank you Dorothy Sayers, for your foresight and your strength of purpose. Thank you all the other writers of my age, who have never given up.